Scientists are “farming” coral reefs in an effort to increase their survival

04/24/2018 / By Ralph Flores

There are a lot of factors that can contribute to the current decline of coral reefs all over the world: This includes pollution, sedimentation, disease outbreaks, destructive fishing practices, and even careless scuba diving, to name a few.

However, scientists are taking up the cudgels in the fight to save coral reefs. In the Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida, for instance, corals are grown in nurseries to be “farmed” later on and transplanted – or “outplanted” as they call it – onto degraded reefs.

The case of the disappearing corals

When people think of corals, the first thing that comes to mind is a thorny structure where many types of fish swim around. That’s partly true, only corals aren’t the structure – but the tiny creatures that latch onto it and make it their home. These are called coral polyps, and these soft-bodied creatures gather by the millions to settle in a limestone skeleton. The resulting structure, called the coral reef, is then fastened by the polyps onto the rocks on the seafloor, where they multiply and spread.

Corals occupy just over one percent of the ocean floor, but their benefits extend far beyond their space. From their development, they form a symbiotic relationship with the algae and bacteria around them. They also function as a habitat for a quarter of all marine life – which explains people’s first impression of corals. In turn, people benefit from the fish found around coral reefs: On average, at least half a billion people depend on reef fish for food.

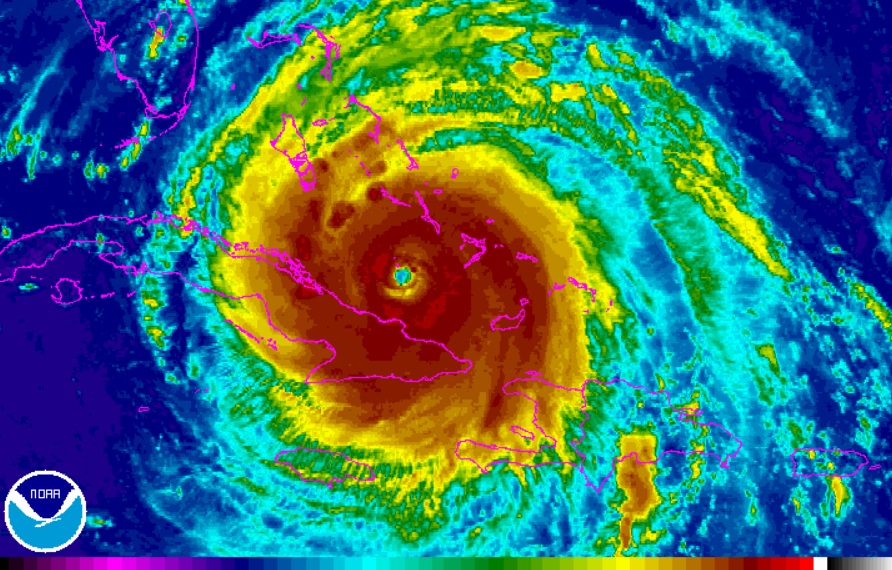

For all their benefits, corals are very fragile. For a reef to form, corals would need at least 10,000 years, and they only increase by a fifth of an inch per year. However, they can easily be damaged by a number of things – agricultural runoff, overfishing, and even the chemicals found in sunscreen. When corals are damaged, they spew out their algae partners and turn “ghostly white” – a process scientists refer to as bleaching. Once this happens, corals will then starve since they lost their primary food source in algae, become diseased, and eventually die.

The death of a coral is not only unfortunate, but it also carries a sinister effect throughout the ecosystem. The once-vibrant reefs turn barren, unable to support the various species that call it home.

The effects of bleaching are widespread: In the past 30 years, at least 50 percent of corals have been lost to bleaching, with the greatest casualty being the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, with at least two-thirds of its coral reef reported to be dead or severely bleached. According to experts, by the year 2050, only 10 percent of corals around the world will remain. (Related: Australia is dealing with the “most severe bleaching event ever recorded” on its western reefs.)

A radical solution in the nick of time

One thing that the corals have going for them is that they can produce either sexually or asexually – a detail which researchers at Mote are using in their conservation efforts. In essence, they deliberately break off corals to create new ones, thanks to coral polyps having the ability to clone themselves. In total, at least 90 species have been farmed in degraded reefs around the world, with thousands of corals being outplanted each year.

According to Dr. David Vaughan, the Executive Director of Mote’s Elizabeth Moore International Center for Coral Reef Research & Restoration, corals exhibit a natural healing response once they are broken into “micro fragments.” This allows them to grow from 25 to 50 times quicker than those in the wild. Vaughan and his team use this effect to “re-skin” boulder corals, encouraging live coral growth over dead coral skeletons.

So far, this effort has been fruitful: Over 20,000 corals have been outplanted in recent years, but Vaughan is looking to have at least a million more by the end of the decade. “I see this technology developing very fast,” he added. “I hope that in 10 years, coral reef restoration will include many organisms and follow the success of forest, mangrove and wetland restoration in being a common, cost-effective tool that can make a worldwide impact.”

Other groups in the scientific community have taken steps as well. In a study published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, a peer-reviewed journal from the Ecological Society of America, researchers from the University of California, Santa Barbara discussed the potential uses of different key ecological processes like predation, competition, and nutrient cycling in coral restoration efforts.

The study, which also referenced the work of scientists at Mote, also looked at how coral restoration can affect other members of reef communities like fish, urchins, and other types of coral. In their study, they suggest that coral restoration be done in areas where there is a high volume of “herbivorous grazers.” With the presence of these types of animals, seaweeds and other plants that compete with corals for space and light are consumed, benefiting the growing coral population. In addition, the nitrogen excreted by fish will provide the symbiotic algae in corals with more energy, speeding up their growth.

Despite all these efforts put into restoring ailing coral reefs, scientists acknowledge that there is no quick fix to this problem. However, in this race against time – and the complete decimation of corals – ensuring that, at the very least, these small and fragile creatures live to see another day could be the break they need to survive.

Do your part in protecting corals by cutting back on possible water pollutants. Learn more by heading to Pollution.news today.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

algae, conservation efforts, coral conservation, coral outplanting, coral polyps, coral reef, coral transplant, corals, environment, herbivorous grazers, marine life, marine species, ocean health, ocean life

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author